In the process of submitting the manuscript for my second book, Tracing the Cape Romain Archipelago, I had the unpleasant task of having to reduce the book’s length. Several of my trips did not make the final revision. The following is a sail to Cape Island on September 22, 2006. Unfortunately photos from that day are lost, and images are from other dates.

Low tide at 2:22 PM. Predicted winds E 10-15 knots, switching to SE later.

Even at 8AM the parking lot at the Ashley Landing on Jeremy Creek was half full. The shrimp baiting season was in full swing. I chatted with an older gentleman who was walking to his launched boat at the floating dock. He recalled how hard the wind blew the previous day, though now there was little wind. As I launched Kingfisher, another boater echoed the memory of that strong breeze.

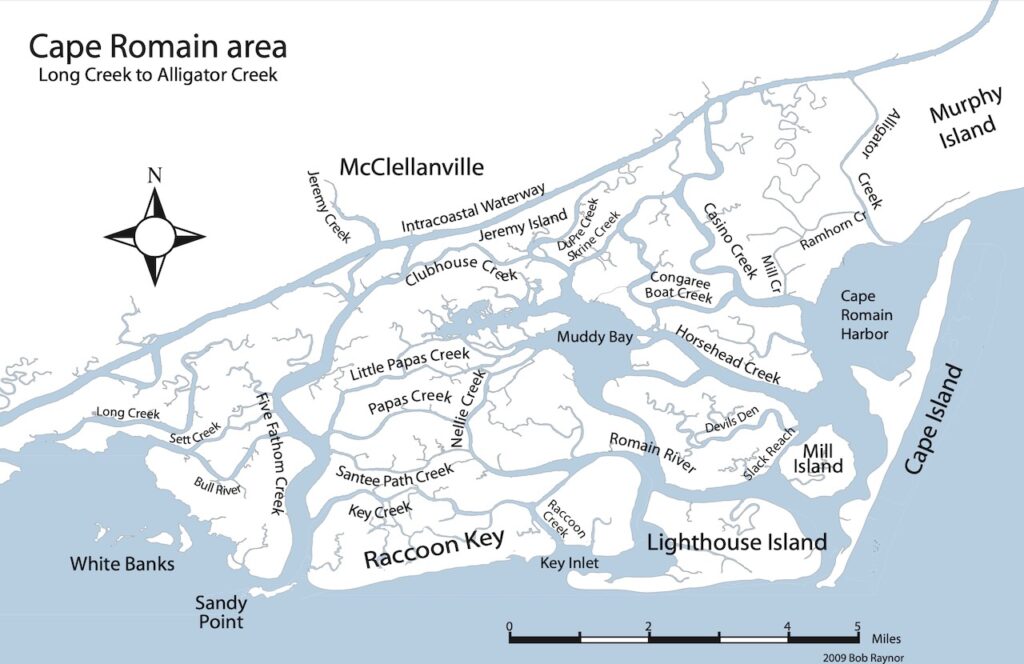

I used the paddle to speed the trip out Jeremy Creek, but once in the Intracoastal Waterway the signs of the developing wind arose, and I began the process of beating up to the entrance to Clubhouse Creek. Once in that waterway I was able to ease off, and the flooding tide did not slow our progress. There was a smattering of clouds, and at one point the sun behind them sent beams out for some radiant moments, a celestial notice of the autumnal equinox.

Flowering Spartina in the morning light enhanced the creek aesthetics. The breeze had filled in fully, and it was fine sailing to windward. I reflected on the many times I had sailed through this same spot just trying to make a passage to the next place. On this day the moments were special – the morning light, the blooming cordgrass, the promise of a trip to Cape Island.

The wind drew us on, and the high tide allowed for carrying each tack right to the grass. We glided past Jeremy Island easily. Away from the tree blanket, the wind strengthened and required hiking out to keep the hull flat. The wind picked up the edge of my chart case, and despite the restraint of shock cord, it flew off the deck and into my wake. The first man-overboard drill was not successful, and though I ran over it on the second go-round it appeared on my leeward side for a grab. The case was no longer watertight, and I emptied all out except for the sodden chart.

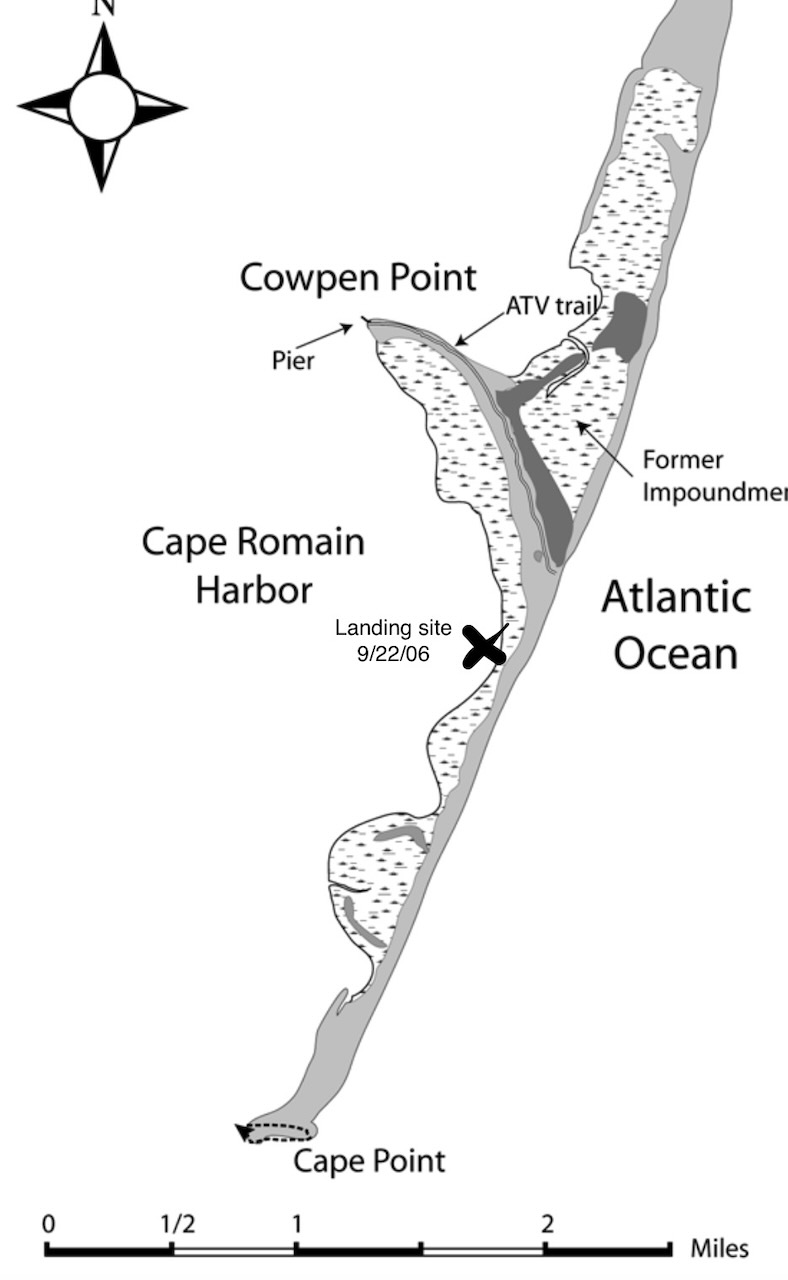

Wading birds appeared – snowy egrets in the marsh, and a great blue heron flying ahead on our same course. Heading out into Muddy Bay, it was time to don the lifejacket, and make a course change. Rather than sail south across Muddy Bay toward Key Inlet, and behind Lighthouse Island to the southern end of Cape Island, I decided to head out Horsehead Creek to the east southeast and across the sound for a landing on the backside of Cape Island, in a place where there appeared to be a break in the marsh populating most of the sound side of the island.

Tacking along the northern edge of Muddy Bay, a workboat was approaching from astern. I stayed along the marsh, and tacked back in, giving him the wide open waters to navigate. Tacking back before the grass, I looked under my boom for him, but was surprised to see him close astern and powering down, then slipping closely aft of me and turning into the narrow creek connecting to the Congaree Boat Creek. The boat had a SCDNR insignia; it seemed a completely unnecessary close interaction of boats with lots of water around.

The wind had risen to the predicted 10-15 knots. Horsehead Creek is wide, and there was plenty of room for long tacks. The opposing east wind and outgoing tide were throwing up a light chop, sending spray over me for cooling, but soon the waves picked up and began to drench me. I chose to hold the port tack out of the channel in the sound toward shallower and smoother water, but the increased wind was kicking up the chop all across the sound. I had asked for wind, and here it was.

My adjusted course necessitated tacking along the marsh on the way out toward Mill Island. I searched from this vantage for a promising landing spot in the cove south of Cowpen Point. I was hiked out fully, and occasionally used the deck-mounted clam cleats to hold the sail’s sheet. Suddenly the sheet burst out of the cleat, heeling the hull dangerously to windward, and immersing me up to my armpits (in my old Laser I would have capsized and been upside down in the water.) Relieved it was not winter, I sheeted back in and sailed on.

We passed the point of Mill Island, where pelicans and cormorants roosted on the top of a shell rake until disturbed by my passing. A long port tack took us on the course toward the large embayment of the island, and a small sandy area appeared. The waters appeared to be quite shallow toward the island’s backside, the chart showing one half to one foot depth, but the relatively high tide would allow making it in for a landing. Feeling the way with daggerboard and paddle, we approached almost to the little beach before rounding up, pulling out the daggerboard, and jumping out to pull Kingfisher up on the sand. The sand was solid underfoot, and I found a small stump to relocate and bury as an anchor point.

Though the crown of the strand did not allow a sight line to the water’s edge, it was a short walk over the beach from the landing point to the ocean, paced off as 150 feet, certainly the narrowest section of Cape Island. There were signs of high tides washing completely over this section of the beach. The ocean was rough, the east wind and Hurricane Irene out in the Atlantic kicking up the surf. I contrasted these conditions with my circumnavigation of Cape Island on September third [See Tracing the Cape Romain Archipelago, pp.99-109.]

There was an ATV track on the beach, surely a loggerhead crew working the south end of the island. I heard the sound coming from the south, and the two riders on the vehicle stopped for a chat: Sarah Dawsey, refuge biologist for Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge (CRNWR), and Michelle Pate, who had interned the previous season. They had completed loggerhead nest protection on the south end of the island, as well as on South Cape Island, and were headed north to complete the survey of the island. Staff and volunteers were inventorying each hatched nest. Sarah shared that there were still one hundred unhatched nests on the island.

It had been a busy nesting season, and that year the total number of nests for all the refuge islands was 1,343. That number compares to the nesting total for 2022 in the refuge of 3,310. A number of conservation efforts have made significant gains for loggerheads along the Atlantic Coast, moving the marine reptile away from endangered status.

I did not know at the time of this encounter that I was talking with future loggerhead royalty. For her considerable efforts with the turtle program, in 2009 Sarah Dawsey would receive the USFWS Regional Director’s Honor Award. A few years later she would take over as refuge manager of CRNWR, which has the highest density of loggerhead nesting north of Florida. Michelle Pate would become the sea turtle coordinator for the state of South Carolina with SCDNR.

I had earlier learned from Sarah Dawsey that this section of the island was breached during Hurricane Hugo in 1989, a physical event creating significant difficulties for the turtle program. In the 1990 season, and until this inlet closed again, the turtle crew would row a rubber raft across this narrow inlet, and then on foot would drag a wheeled cart down the beach to the south end. They would then come back picking up each nest in the cart, load and row back across the inlet, and take those buckets of eggs to the hatcheries at the north end.

This section of Cape Island would breach again in 1996 by Hurricane Bertha, skirting the coast. And breach again in 2011 when impacted by the waves and tides of Hurricane Irene offshore. And the break would widen – at the present there is no sign of it filling back in. North Cape Island and South Cape Island are now discreet entities. The former Cape Island had lost over two miles of its length.

After saying goodbye to Sarah and Michelle, I continued my walk to the south. An area ahead on the island’s backside had intrigued me in the past while doing nest protection, and I wanted to take a look. The half-round bulb on the island’s backside had a slight elevation rise on one side conducive for the growth of cedars and yuccas, and I found a segment of a dune devil-joint impaled in the side of my foot above my sandal. I retreated back to the beach, noting an occasional caged loggerhead nest not yet hatched out.

Returning to Kingfisher, I moved her to a steeper section of the landing area due to the fast receding tide. A dozen and a half oystercatchers flew off on my approach. Walking north, there were various botanical communities – a “lawn” of glassworts, fairly sizable sand dunes with sea oats, and mounds of seaside spurge. I planned to sail off after a brief lunch.

A large oyster rock had appeared as the tide had gone out, and other features were popping up above the surface as I rigged up. It was clearly time to shove off before being locked in by the outgoing tide. Dragging Kingfisher down to the water, I began to sink in the mud up to my knees, and felt periwinkles between my feet and sandals. I used my weight on the hull to push and pull until she floated. The water was about six inches deep, so I let the wind blow me off the shore with the help of the paddle.

Finding a little deeper water, I dropped the rudder, but the boat would not round up for sail raising even with the helm over. I used the paddle in a hard cross draw stroke, and managed to tweak my lower back, an old injury and chronic problem. There was nothing left to do but hoist the sail, make it fast, and bear off. I carefully sailed at partial speed across the mud flats, fearful of hitting a submerged object.

We made it to open water, and reached across the sound. I had taken a compass bearing from the beach, and steered accordingly. There was still some outgoing tide, but the solid breeze made progress rapid. It was still early in the day, but my back spasm eliminated ideas of extra adventures on the homeward sail: across Cape Romain harbor, through Horsehead Creek, across Muddy Bay, through Island Cut and Clubhouse Creek, and back into the ICW and Jeremy Creek. I wasted no time dropping sail and coming into the dock for a quick haul out, avoiding the gridlock of a busy landing day.

Loggerhead nesting is off to a rapid and robust start on the Cape Romain islands in 2023. I hope to get out to the islands this summer for some of that nesting action.

Thanks for sharing and I loved the maps and digital footprints for reference!

Hope to have my footprints out there this summer.

Having seen the breaks in Cape Is for ourselves, we have been equally concerned regarding availability of habitat for a successful turtle nesting season..

It is amazing that with the reduced island size the numbers have been so high as in last year’s numbers. Something has to give.

Enjoyed our evening and continued conversation of the Santee Delta and Cape Romain refuge. Love learning the names of the different islands from your maps. Seems Oyster Bay is now Muddy Bay. Hope the turtles will have enough space on Cape Island.

Good to know we have expert biologists on the job and you and The Kingfisher always checking and researching. Keep up the good work. Dana

Oyster Bay I believe is a smaller body of water off of Muddy Bay. The loggerheads are finding nesting beaches, with more nesting on Lighthouse Island. Somehow, they keep reproducing on eroding beaches.